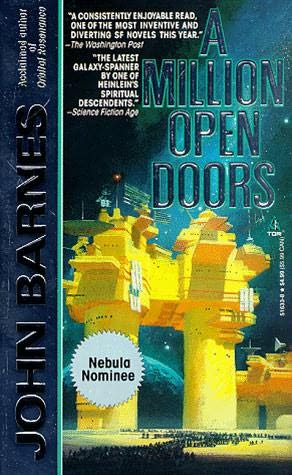

A Million Open Doors is a wonderful immersive science fiction novel. John Barnes is an important writer, and this is perhaps his best book. It’s set about a thousand years from now, in a future history that plausibly is intended to start from here. There’s a very interesting article in Apostrophes and Apocalypses about how Barnes made up the universe, which I’d highly recommend to anyone interested in worldbuilding. The history feels like history—a number of reachable terraformable planets were settled, then outward colonization stopped. Some of the cultures that settled the available planets were very odd indeed. Now the “springer” has been invented, a matter transmitter that works between worlds, and humanity is back in contact and expanding again.

A Million Open Doors opens in the culture of Nou Occitan on the planet of Wilson. And it opens in the engaging and self-centred point of view of Giraut (that’s pronounced “gear-out,” Occitan isn’t French) a jouvent, a young man who is part of the youth culture of the planet, devoted to art and duelling and “finamor,” passionate but empty romance. Through Giraut’s eyes, Nou Occitan is fascinating and romantic. Springers reached it about ten years ago, and are slowly changing everything. One night Giraut’s drinking with his friend Aimeric, a refugee from the culture of Caledonia on the planet Nansen, when the prime minister of Nou Occitan turns up to explain that Nansen has opened up springer contact, and the Council For Humanity would really like him to go home to help. Giraut goes with him, and we see the second culture of the book, the city of Utilitopia on cold hostile Nansen, where everything has to be rational by rules that look very irrational indeed.

Barnes sets it up so that the two cultures reflect each other very well, so that Giraut illuminates cultureless Utilitopia with Occitan art and cooking while realising through Caledonian sexual equality and non-violence that his own culture is really not a very nice place for women, and perhaps their constant dueling is really a little much. Both cultures have strange things wrong with them. Both cultures are fascinating, though I wouldn’t want to live in either of them. On Nou Occitan, artists describe the planet as it will be when the terraforming is finished—there are songs about forests that have only just been planted, and no paintings of what things actually look like now, halfway through the terraforming process. In Caledonia it’s considered irrational and immoral to do anything for anyone without being paid for it. They’re both interestingly weird, and they’re both having problems caused by the new springer technology.

The political and economic maneuvering around the opening of the springers and contact lead to excitement, new artistic movements, and new fashions on both planets. The events in Utilitopia can be seen as “SF as fantasy of political agency” but I don’t think it’s a problem. Giraut finds something to believe in, and something to write songs about. Eventually, by accident, they discover ruins that might be alien or might be unimaginably ancient human ruins. (“Martians or Atlantis?” as an investigator puts it.) At the end of the book Giraut and his new Caledonian wife are recruited into the Council for Humanity with the hope of bringing humanity together even as it fragments again in a new era of exploration and colonization, and bringing it together with grace and style rather than bureaucracy. This is a wonderfully open ending. You don’t need any more, but of course you think you want it.

If Barnes had stopped there, I’d be able to point at A Million Open Doors as a pretty much perfect example, almost a textbook example, of the subgenre of science fiction I like best. It’s a really great well-written book. It’s set in our future. It has fascinating anthropology. It concerns the introduction and implications of a new technology. It has nifty ideas. It has great characters, who grow during the story. It opens out and out. It has at least the possibility of aliens. And it’s a hopeful vision—not a stupidly gung-ho vision, but a positive one.

Unfortunately, the later Thousand Cultures books fail for me. It isn’t so much Earth Made of Glass, though I know a lot of people don’t like it, and it is a bit of a downer. Earth Made of Glass is about Giraut visiting two other (brilliantly depicted, fascinating) cultures which in the end destroy themselves. (It’s like that joke about “Join the army, travel the world, meet interesting people and kill them…”) It’s that after that, in Merchants of Souls and The Armies of Memory Barnes appears to have decided to reimagine and retcon both the world of Nou Occitan, occasionally actually contradicting what’s said in A Million Open Doors, and the central significance of what the series is about. These later books are about the “problem of leisure” (which strikes me as as much a non-problem as the Singularity) the pointlessness of people’s lives when AIs and robots can do most of the work, to such an extent that humanity seems like it isn’t worth bothering with after all, and as for the aliens, and the new expansion, that’s all retconned into irrelevance. I’m afraid that on re-reading and reflection and seeing these as a completed set, I have to give the advice people always give about the reading order for the Dune books. “Read the first one and stop.”